I loved the book Hunt, Gather, Parent by Michaeleen Doucleff, but there were some suggestions in the book that made me skeptical when I first read them, including the section title “Discipline without Words.” My immediate response was dismissive as though it would be impossible to discipline a child without words. When I considered the levels of conflict in my home though, I decided to try it for a few days. It wasn’t going to hurt anything, and it seemed to work so well for the communities described in the book.

I have a quick temper, so I was the source and the model for a vast majority of the conflict in our home. Even when it was only the children who were arguing, I had not demonstrated a good example of how to handle strong emotions with self-control. Because I was the epicenter of the conflict, changing my own actions would potentially change the entire atmosphere around my house.

The author of the book detailed the number of times hunter-gatherer communities command their children (2-3 per hour) as compared to Western parents (1 or 2 per minute). We tend to tell our children what to do and what not to do constantly. Someone is always talking, which disrupts the potential for peace and calm. Based on this information, I resolved to be silent for longer periods of the day, guide my children’s actions without words when possible, and issue fewer commands when possible. Here are the results of my experiment:

Eliam is a very distractible kid. If he doesn’t obey, it is as likely that he completely forgot the instructions as it is that he is being willful. He can be walking down the hallway to get dressed, see a lego on the floor, sit down, and play with it for ten minutes. Normally, I would repeat“Eliam, go get dressed.” “Eliam, we need to leave.” “Eliam, do you have your clothes on yet?!” “Eliam, we have to leave!” in a steadily escalating voice until I’m yelling at him from the other side of the house. This was the perfect opportunity to practice guidance without words.

At one point, I told all the kids that we would be leaving soon, and everyone needed to wear clothes, socks, and shoes in order to go. The book describes Inuit communities who don’t even have to give these instructions. The adults get ready and walk out of the house, and the children are trained to follow the modeling of the adults. We aren’t there yet, so our interactions started with the command. Ana Lia got herself ready, and I got Finiasi ready. Predictably, Eliam was still walking around the house in only a pair of shorts. Instead of saying anything, I looked him in the eye and gestured toward his room with a look clearly indicating that is where he was supposed to be getting dressed. To my surprise, he went there immediately and put on his shirt. When he returned to the living room, again without any words, I handed him his shoes, and without any words he put them on. This single interaction opened my mind to the vast opportunities to use this throughout our days.

The more I employed “Discipline without Words” the more effective it became, and I found that I was getting angry much less frequently. I was calmer, and the kids were cooperative. Of course, it wasn’t a perfect utopia, but if I compared the volume of our emotions (me and the kids when Afa was not home), it went from an 8 on most days down to a 3 over a week or so. The difference was visible and drastic. Here are a few other examples of when I chose not to use any words to the benefit of everyone involved.

I was working at my desk, and the kids were playing cards in the living room. Finiasi was not playing the game right, and Ana Lia was getting angry with him. They started arguing. In the before times, I would have again started with a short command and increased my volume until I was angry and yelled at them to go outside and leave me alone. Instead, I stood up from my desk, walked over so that they all looked up at me, and looked all three of them in the eye very slowly. Then I silently walked back to my desk. The argument ceased.

Another time, the kids had gotten a large tub of ice cream out for our morning ice cream break. The older two had left it on the table, and Finiasi wanted to put it back in the freezer. It looked like it was far too heavy for him, but instead of telling him that I would put it back, I sat in silence. He worked for several minutes to drag it all the way across the kitchen floor. He opened the freezer, but could not lift it to one of the empty shelves. He asked for help, and I walked over and lifted it for him. I didn’t interfere with his work and his attempts to contribute. I allowed the interaction to progress quietly.

At a different point, I needed the kids to pick up the living room, and again, this often began by yelling at them to clean it up. This time, I modeled what I wanted them to do. I started picking it up myself and then gave them specific jobs – Ana Lia to clean the books, Eliam to get the clothes, and Finiasi to get the toys. I only gave the verbal instruction one time. I kept picking up random items to show that we were doing it together, and when one of the kids stopped their task, I picked up the right item and handed it to them. Without any additional words, they understood what they needed to do with that item. Another common source of conflict became a five minute opportunity of cooperation.

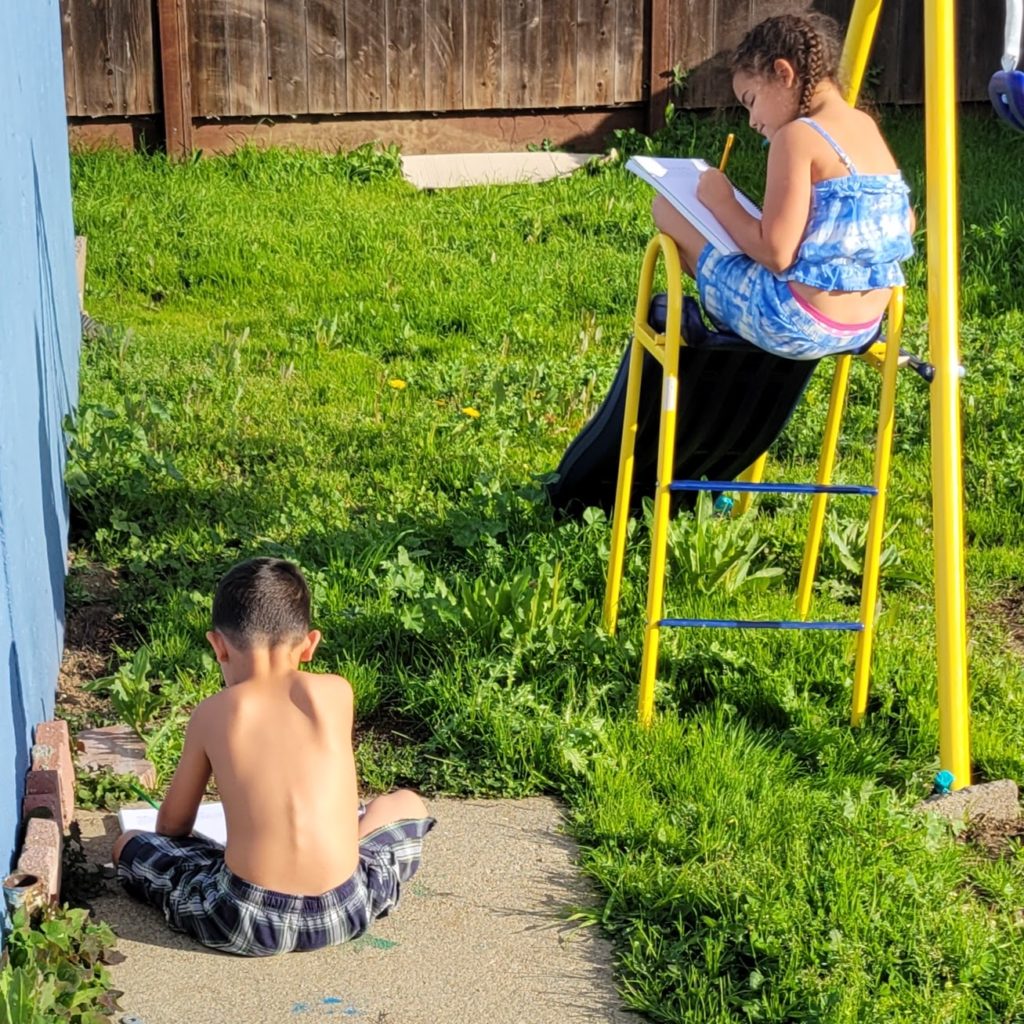

In a separate argument that the kids had while playing outside, Finiasi started screaming. I would normally jump up to figure out what was going on, especially because it was disrupting my work time, but I held back a moment, took a deep breath, and waited to see if they would work it out on their own. They managed to calm everyone down, and I didn’t even have to stand up. My plan had been to walk outside silently again, but I realized there are times when they do not need my intervention at all. I can allow them to resolve their own conflict as long as no one is getting hurt.

Before I started, I was afraid that talking less would decrease my opportunities to connect with the kids. Logically though, if I use fewer words overall and the words I cut out are the unnecessary commands issued to my children, a greater proportion of my words will be related to connection rather than correction. They will be getting more of the mom that adds to their life, which is always my goal. As I practiced, I found this to be more and more true. When I was mindful of the words that I used, a larger percentage of those words were calm, kind, and encouraging, even in the moments when those words were corrective or instructive.

This is a skill I am going to have to practice over the long term because I am so accustomed to talking all the time at home. But I have found peace in the silence, and I will continue to bask in that peace in my home – without all the words to disrupt it.